Book Review: Unraveling the Art of Tapestry

Submitted by sharragrow on

Review by Katja Diaz-Granados

Anatomy of a Tapestry: Techniques, Materials, Care

By Jean Pierre Larochette & Yadin Larochette, illustrations by Yael Lurie

Pennsylvania, USA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2020

160 pages / 190 images and drawings / $45.00 / Hardcover spiral

ISBN: 9780764359330

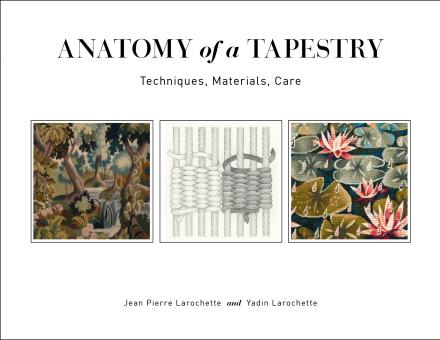

I can’t claim to be an expert on weaving. My experience is limited to a loom fashioned out of a piece of cardboard with slits cut to tightly fasten the warp. What drew me to this book was as much its cover, with its vignettes in muted verdant colors, as the novelty of seeing a book dedicated to the art of tapestry let alone one with a conservation focus. The authors, Jean Pierre Larochette and his daughter Yadin Larochette, accomplish the remarkable task of writing a book that is part instruction manual for the aspiring weaver, part philosophical musing on the history and role of tapestry in various cultures, and part technical treatise on the material properties of woven textiles.

This is not a text for the faint of heart. To describe the passage of the weft in and around a backdrop of evenly spaced warp fibers is a task difficult to accomplish with words. As Jean Pierre points out in the preface, weaving is a kind of tacit knowledge built from years in the workshop and with terms that borrow from languages across the world. A glance at the book’s glossary can attest to the fact that the “bobbin” is one of the more ordinary terms the reader will come across, with “galloon,” “gobelins” and “grattoir” being a sampling of the g’s alone. Needless to say, the technical illustrations included are a boon. These are simple graphite illustrations that loosen and enlarge the intertwining threads so the reader can trace a finger across the thread, following along like a student might follow unfamiliar words in a reading primer.

The authors also offer a sampling of full-color images of finished tapestries, including those of historical significance and examples from contemporary artists across the globe. As is apparent in the included images, weaving is a medium that lends itself exceptionally well to the creation of illusions. Scale is an integral part of this, with large-format works blurring into seamless images (provided, of course, that the weaver has taken a thoughtful approach to the shapes being built up). The chapter on weaving techniques exposes much of the underlying planning that goes into the creation of curves and contours, as well as precise angles for sharp corners. Shapes that, at the offset, seem impossible to achieve with the block-like steps of a weave can be mimicked with the appropriate sequence of turns. The pattern with which the weft is passed around either a covered or bare warp dictates how shallow or steep a step is created, and Jean Pierre has compiled a kind of recipe for creating the desired shapes. A triangle with a mirror plane of symmetry should be woven on an odd number of warps, and a steep contour requires a three-pass step, followed by a three-pass step on the covered warp and a four-pass step on the bare warp. In some ways the book presents tapestry weaving as less of an expressive endeavor and more of an engineering feat.

This is not to say that the authors portray a single technique as the sole, correct method of weaving. According to Jean Pierre Larochette, a specific loom and the weaving created on it are as much a reflection of the available time and materials as they are of the final design. The history of the tapestry loom is riddled with examples of portable looms that could be assembled and dismantled for weavings that were the culmination of a season of fiber preparation. Particularly informative for the textile conservator is the insight the authors offer on how the choice of loom and weaving technique will influence the final weave structure.

I began reading Anatomy of a Tapestry with the impression of tapestry as a relatively robust artifact. Tapestries were, after all, used as early forms of insulation for medieval castles—albeit rather decorative ones. I found it surprising, then, just how cautious a textile conservator must be in their choice of reinforcement material. Knots are generally avoided when repairing tapestries, as are polyester threads, since both can potentially cut into the original threads. When a loss in the tapestry requires an area to be rewoven, not only should the new thread be compatible with the old, but the conservator must do their best to match the tension of the original weave. This was one area of the text that I felt was deserving of a more complete description. Having just read the chapter on loom design, it was difficult to imagine how new warp and weft threads could be simply anchored into the gaps of a damaged tapestry.

What Yadin does offer is a comprehensive list of alternate methods for creating in-fills, mentioning the possibility of painted patches that can be sewn in, as well as describing techniques employing software to print a rep weave* fabric. The same emphasis on completeness is found throughout the book’s chapters on tapestry care, where best practice is laid out for stewards with varying capabilities. Yadin makes explicit reference to state-of-the-art materials used for storage and display in the most well-equipped museum but takes the time to also offer suggestions for the more modest display of tapestries in the home. This was an unusual inclusion, and one that I have not often seen in conservation texts.

The appreciation for tapestry in all its forms, whether woven on a loom of matchsticks or a basse-lisse loom of the Aubusson tradition, is apparent in every page of text. So contagious is the family’s enthusiasm for tapestry (for the book is indeed a family effort, with Jean Pierre’s wife responsible for the illustrations and his father for many of the tapestry designs), that the reader cannot help but feel drawn to search out a tapestry. This is encouraged by the authors, who are emphatic in their assertion that a tapestry is best understood in person; only then can the way the woven surface scatters light, offers warmth, and dampens sound be understood.

AUTHOR BIO

Katja Diaz-Granados is a PhD candidate studying Interdisciplinary Material Science at Vanderbilt University. She is interested in applying near field spectroscopic techniques to characterizing the materials used in works of art.

NOTE FROM IIC BOOK REVIEWS COORDINATOR, ALEXANDRA TAYLOR

Anatomy of a Tapestry is wonderfully reviewed here by Katja Diaz-Granados. Her admiration for woven textiles is evident in the way she observes certain aspects of the book, chiefly the included methodology of weaving. I am particularly drawn to her sensitivity in describing the reaction between material and ethereal properties—of the way a texture scatters light and the historical significance of tapestries. Katja just touches on the intangible in her thoughts on Anatomy of a Tapestry which reminds me of another author interested in exploring this aspect of textiles. Rania Kataf is an independent researcher, photojournalist and storyteller in Damascus. You can read my own thoughts on her essays and advocacy efforts surrounding traditional Damascene textiles in this issue’s Letters to the Editor, (February-March 2022, "News in Conservation" Issue 88, page 66.)